In the Wings, Brook Hall, November 2015

In late September, I posted on social media that the government of Taiwan, after long deliberation, had made significant change to the work permit conundrum of foreign performers. More than five hundred people responded favorably to the post. When I got the news from the law team that lobbied on our behalf, and from Ping Chu’s advocacy group, Forward Taiwan (of which I was a taskforce member), I was sitting, looking at the water on the East Coast. I immediately jumped up and danced for joy. The old interpretation of the law had been an absolute albatross; the “cost” of living on a beautiful island with great people; and, the final insurmountable frontier to making a life as a full-time performer/director a possibility.

While performers could live in Taiwan, they could not perform unless they prepared about twenty documents in a folder, stamped them with the appropriate stamps, got the appropriate permissions, and spent a solid week navigating the always-changing, opaque requirements and procedures for each performer, performance, film, song, or dance. Few foreign performers are told about the necessary paperwork, and a scant handful of local companies have the knowhow or desire to apply for it. When I asked a local agent if he could get one for a recent commercial they replied “Why would I go to that trouble for one day of shooting?” Yes, why indeed? Of course, the local film industry, which employs the most foreign actors, had given up on following this regulation years ago.

It should be known that matter at hand isn’t a “law.” It is an interpretation of the law–a “regulation”—which Taiwan considered a necessary evil to protect its own performers. The rules were made intentionally difficult to prevent the loss of Taiwanese performing jobs to foreign singers from the Philippines, who dominated the entertainment industry in the 90’s. Unfortunately, this long-held interpretation has created a rather toxic situation. A situation that, at times, caused me to doubt my decision to move to Taiwan, and resulted in many of my professional peers leaving, or deported.

It took a few weeks before the ruling was made clear. The gift from the current government allowed foreigners to gather and put on a show, get on a stage, sing a song, or read a poem without fear of deportation as long as they are not paid, and they are not working with the venue management. So let’s celebrate, for a moment, the once-in-twenty-years attention to this issue. In 2001, no one cared a whit about foreign performers or their complaints. In fact, the only foreign work permits issued were for the big jazz bars in the international hotels.

While this is a long-overdue move in the right direction, the barring of professional performers who earn stipends, unfortunately, makes it abundantly clear we are not considered valuable to local society. The recent ruling was a consolation prize; a token of understanding. It is necessary for quality of living for the part-timers, and it is welcome. Even so, much more can be done for local professionals who can make a real impact when given the freedom to do so.

There are too many stories experiences to fit in this article, but I would like to share a few which illustrate the depth of the problems these regulations cause. In 2001, I was invited to participate in an international arts festival in Southern Taiwan. My friend C, who invited me and led the festival, warned me when I arrived. “You will like it here, but you can’t stay here. The government won’t let you do what you want to do.” I have always appreciated a challenge, and I was just coming off a Broadway National Touring musical with my Actors Equity Card, several directing/choreography credits to my name, a resume of big name co-star/collaborators and bag full of big dreams. But he was right. The government won’t let you do what you want to do, and, as a corollary, they do not understand what kind of impact you can have.

After running into problems getting permits and starting a theatre company, my friend C could not take it and left. Taiwan lost a professional producer and director with many international credits. He now serves as Resident Artistic Director for THE HOUSE OF FALLING WATER-「水舞間」in Macau- the biggest show ever in Asia – and Taiwan’s loss is Macau’s gain. (Taiwan’s government recently invited the show producers of 水舞間 to Taiwan to learn how Taiwan could make something similar. If only they knew.)

As for my small part, having worked with several major local theatre companies, I see my fingerprints all around. Pick up any current local theatre direct marketing flyer (DM), especially in the area of musical theatre, and you’ll find a popular leading actor that I had a part in training. Dancers I used to hire or teach are now choreographing and using my style. My director style is now employed by my former actors. Triple threat actor/singer/dancers are now standard after the hoopla caused by my production of SMOKEY JOES CAFÉ in 2008. In fact, the director and producer of the perennial tour of MY DEAR NEXT DOOR (2010-present) called me while that show was in production and, just like ‘SMOKEY’ before it, that show has a big 60’s style partner song/dance in the second act. Furthermore, sailors entered the common show language, started appearing in music videos, local product launches, and lingerie fashion shows after my production of ANYTHING GOES at the National Concert Hall and the International Trade Center. I brought Broadway performers over to work with locals in that show. Now at least four of the Taiwanese locals I cast are in New York, making an impact, representing Taiwan. I have directly helped an additional six local actors get into prestigious university performing arts programs. All of this happened while I fought to stay in this country, making visa runs every two months. “Visa run in the morning, lead a National theatre dress rehearsal at night.”

I share these not to highlight my resume, but to demonstrate the impact foreign and local workers can have together when allowed to collaborate. I have since been contacted over twenty times by email from abroad. The opening salvo is the same: “I hear you made a life for yourself as an artist in Taiwan. How can I go there and do what you did?” My truthful answer is “You can’t. The government won’t let you do what you want to do.” One such “You can’t” recipient from Korea decided not to listen to my advice. M came here and, right away, gathered a group of performers, put on short plays, found venues, and made a name for herself. She continued for many years and many nights of short plays. Eventually, she and I co-produced the musical TITLE OF SHOW. Unfortunately, M couldn’t take the chorus of “nos.” For ninety percent of available venues, the government refused to allow foreign work permits, and made it difficult to acquire the required documents, such as re-modeling documentation, and tax compliances, for ninety percent of the venues. All of these issues and more led to M leaving Taiwan. Taiwan lost yet another amazing artistic asset when she did.

M did not start the company alone. She had a partner, S. S was a promising young actress and her story is one of legend. One agent or manager (no one knows for sure) had a grudge against another agent. S was an extra actress in a Television commercial, and the real insidious side of these regulations reared their head. You see, if you know a performer is working without a performance work permit, you can report that person and earn a substantial financial award. In the case of S, she got caught up in the grudge and a call was made to the authorities. Those Taipei authorities have since said (direct quote) “We do not want to investigate foreigners performing illegally, but if we are called, we have no choice.” So, foreigners are often wrapped up in a risky situation: local producers say “Why should I go through the trouble for one day’s work?” and papers are not filed, or one of the myriad requirements isn’t met and permits are not issued and the project goes forward. IF the foreigner is reported, the foreigner can be punished with deportation. That was what happened to S. The company founded by S and M was no more.

The loss of C, M, and S by Taiwan only scratches the surface of what these twenty year-old regulations have wrought. For years, it has been those of us that are most vulnerable who try to get clarity on the regulations. It has been those of us with the most to lose who push for local companies to know and follow the laws. In seeking to do the legal thing, we are often punished. M ran into real problems when the witch hunt for local performers who dared play a song in a local bar created enough fear to cancel a show forty-eight hours before curtain. These venue challenges M encountered kick started the most recent outcry and media coverage of the impossible work permit situation. Forward Taiwan got involved soon after. After examining the facts, and the sacrifices foreigners made to stay in Taiwan, the government responded with its mini-gift. If it takes a long view, though, and is serious about improving and helping Taiwan stay competitive and educated, changing the albatross will encourage more talented foreigners to come and even more to stay and share their gifts. They are in the wings. They are waiting to take the stage.

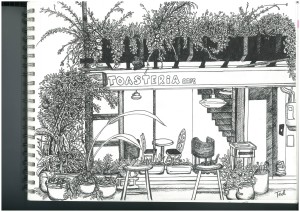

Brook Hall currently serves as the Artistic Director of 實演場 The LAB Space, Taipei’s only international residential theatre company. More information about its mission and its events can be found at www.thelabtw.com . A book about his 15 years in Taiwan show business is in the works.